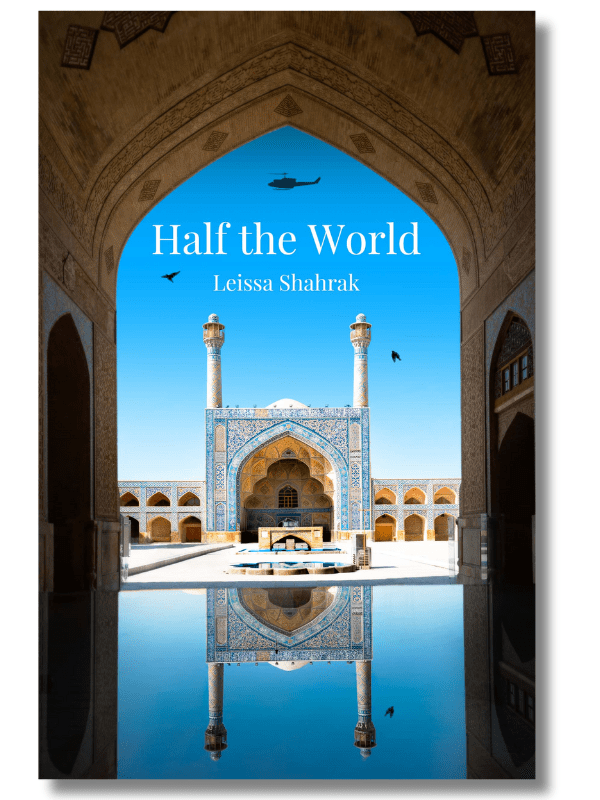

Half the World

by Leissa Shahrak

Genre: Historical Fiction

ISBN: 9798891323803

Print Length: 292 pages

Publisher: Atmosphere Press

Reviewed by Peggy Kurkowski

An enchanting historical novel set in a deeply suspicious society ripe for rebellion

In 1977, newlyweds Angela and Doug Weston arrive in Iran for an opportunity to build a nest egg and enjoy the beauty of Persian culture, but they are not prepared for awaits them in Half the World.

Touching down in the arid, yet starkly gorgeous desert of Esfahan, Iran, the Westons are eager to break away from their pasts and forge a new future together.

Doug, an architect, is leading a construction project for Esfahan’s first technical university that promises a hefty bonus if completed on time. Angela, meanwhile, accepts a teaching position at the University of Esfahan, teaching English to Iranian students. Mixed into their excitement for their two-year stay in Iran is an underlying doubt: can they survive here?

For Angela, “Persia and Persian evoked the exotic—spices, nightingales, roses,” and a popular saying the couple soon learns is that “Esfahan is half the world,” meaning the city contains half the world’s beauty. It is a beauty that will test them both, however, as a ripple of tension seethes beneath the cerulean skies and the archways of the blue dome of the historic Shah Mosque.

Why? The country’s citizens are under the tyrannical grip of Reza Pahlavi, aka the Shah, whose dreaded secret police, the SAVAK, will round up anyone deemed a threat to the regime. Unmarked, yellow buildings are the silent symbol of the Shah’s repression, where those arrested are taken for interrogation and torture. Doug and Angela are nominally aware of the fraught nature of Iranian politics but still try to make their new life work despite the suspicious stares of many (the U.S. supported the Shah’s rule).

Into this bubbling pot of political crackdowns, Shahrak drops the unsuspecting couple and soon the inevitable clash of cultures begins. Doug has trouble with his lackadaisical workers and vents his frustrations through alcohol and prejudicial rants, while Angela strains to make headway with a troublesome student named Hossein Rahimi. Indeed, it is the embittered Hossein—whose father died at the hands of the regime—who is the catalyst for the book’s action.

Interestingly, Hossein is also a stranger in Esfahan, wondering like the Westons if he can survive here, having moved from his tiny village to attend school. His shady roommate, Ahmad, works on Doug’s construction crew but is also a part of an underground revolutionary network.

Soon, he and another accomplice recruit Hossein to help make Angela’s life miserable as the only American teacher at the university. The goal is to rid the country of Americans and their influence, which they believe will help usher in the overthrow of the Shah.

Shahrak’s pacing is well-measured as the narrative moves between these three characters, and we see the deleterious effect culture shock has on the Westerners almost immediately: Doug, a Vietnam veteran, has bouts of PTSD, and Angela suffers reoccurring memories of a traumatic childhood event. Shahrak is at her best exploring each characters’ internal thought processes, which Angela reflects on philosophically:

“She used to believe people gained insight from exposure to the foreign, the unknown. Instead, it seemed their darkest quirks bubbled to the surface, side effects of isolation and the unfamiliar.”

For Hossein, the “darkest quirks” are an inability to control his anger—which Angela fears is a neurological condition—that he tries to balance with his devout Islamic beliefs in hospitality and showing kindness to the stranger. But when Angela, against Doug’s wishes, naively oversteps her boundaries as a teacher to help him, how will Hossein react? Will he understand she wants to help, or will his nefarious associates push him into a life-altering action? Shahrak leaves plenty of mystery to keep the pages turning.

This is an authentic story, lushly told, perhaps because Shahrak herself taught English in Esfahan and experienced the Iranian Revolution firsthand. Her depictions of pre-Revolution Iran with its walled gardens, majestic mosques, and the squalid living conditions of the have-nots of Esfahani society are well-drawn and compelling, painting a portrait of an oppressed society on the cusp of overthrowing the shackles of one regime, only to choose the shackles of another, theocratic one under the Ayatollah Khomeini. Her wonderful grasp of the Persian language is on every page, with Angela musing on how language often carried “a cultural DNA [whose] minute linguistic subtleties separated humans of different classes and cultures.”

What makes Half the World so enchanting is not only Shahrak’s fertile prose and convincing characters, but her obvious love of Persian society and culture that blooms on every page, leaving a whiff of bittersweet nostalgia for a world that no longer exists.

Thank you for reading Peggy Kurkowski’s book review of Half the World by

Leissa Shahrak! If you liked what you read, please spend some more time with us at the links below.

0 comments on “Book Review: Half the World”